Materials Management

Two broad materials management strategies are explored here: dealing with particular materials that are high priority because they have either high global warming potential or high potential to sequester greenhouse gasses, and dealing overall with the materials management system to achieve deep emissions reductions and orient the system towards zero waste operations and a circular economy.

Priority Materials: Refrigerants, Building and Structural Materials, Organics

Refrigerants

Many of the refrigerants in use today are powerful greenhouse gases, an invisible source of air pollution with global warming potentials hundreds or thousands of times more powerful than carbon dioxide. HFCs, which are used for cooling and refrigeration, as well as for foams, solvents and fire suppressants, comprise 6% of the state’s greenhouse gas inventory. Because these gases are in ever-widening circulation as heat pumps become the dominant mode of heating and cooling, New York and the Hudson Valley will not be able to reach their short- or long-term climate goals without addressing HFCs. This has been recognized in the Scoping Plan, which says:

NYSERDA, DPS, and DEC should coordinate to develop incentives such as utility rebates and grant programs to support the adoption of natural refrigerants in food stores. Incentives are particularly needed to fund a substantial portion of the installation of new equipment in existing stores in Disadvantaged Communities or stores operated by independent companies or small chains, to enable food stores to phase out HFCs without impacting LMI consumers or negatively affecting food security.

There is also a need for leak prevention and repair support for food establishments that use large-scale refrigeration. Only about one-third of NY supermarkets have automatic leak detection systems, which have been proven over the years in the EPA’s voluntary GreenChill Program to cut leak rates in half. If a full-size grocery store spends $14,000 to $16,000 on this equipment and reduces its overall leak rate by 10%, the investment pays for itself through reduced refrigerant costs while avoiding CO2 equivalent emissions of 780,000 to 1.3 million pounds each year thereafter. NYSERDA should create a program to support these investments with financial and technical assistance for food establishments in Disadvantaged Communities and for stores operated by independent companies or small chains.

The Scoping Plan also discusses Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs for many products, including refrigerant-containing appliances and refrigerants themselves. Under an EPR program, the producers of a product are responsible for all elements of the product from cradle to grave, which incentivizes them to design for safe reuse or dismantling into useful components and capturing problematic elements at the end of a product’s life.

An EPR for refrigerants would primarily focus on greater rebate incentives for HVAC contractors who should already be recovering refrigerants in following industry best practices and EPA regulations (but frequently do not because of the time and trouble involved).

An EPR for appliances would primarily focus on getting refrigerant-containing consumer appliances (such as window air conditioners and refrigerators) into the hands of qualified recyclers, who will recover the refrigerants before recycling the other scrap metals and materials in the appliances. At present the overwhelming majority of these appliances go directly to landfill or are handled by scrap metal collectors who frequently vent the refrigerants when they harvest the scrap metals that they get paid for. Because these appliances have the most intensive greenhouse gases of anything in New York’s waste stream, an EPR program for these appliances should be prioritized by the waste community in NYS and advocated by the region; it would be fiscally prudent for New York to work with the producers of these products to fund future refrigerant management efforts.

Workforce development efforts are greatly needed in order to have satisfactory numbers of trained personnel who can scale up heat pump adoption in residential and commercial buildings and who can install and maintain state-of-the-art refrigeration equipment in food establishments. All of these new workers will also need to be prepared to maintain legacy equipment in an industry that is working through significant changes.

A strategy for building awareness of refrigerant issues and showing what can be accomplished by pure people-power is the community refrigerant capture event. Red Hook began this in the Hudson Valley in partnership with Bard College, training a group of skilled volunteers to withdraw and recycle the refrigerant in each week’s dropped off refrigerators, air conditioners and other appliances. The model has been emulated in Sustainable Warwick’s “Coolest Recycling Drive,” first held in the spring of 2023 and collecting 130 appliances. Scaling the model up would involve spending about $6.50/metric ton of CO2 equivalent. In the spring of 2024, New Yorkers for Cool Refrigerant Management and Sustainable Hudson Valley held a demonstration collection drive in Ulster County and Warwick, collecting over 500 appliances; the partners will advocate for these collection services to be grown as programs with allied enterprises, as envisioned by proposed EPR legislation before the New York State legislature (S6105B/A10624).

For New York to meet its 2030 goal it needs to reduce emissions by 92,000,000 metric tons annually; if that were done solely by capturing refrigerants, it would only cost ~$600 million/year – shockingly less than many climate budgets under discussion. This suggests refrigerant management is a highly cost-effective climate solution that deserves high priority.

Construction Material

Construction materials such as concrete, steel, and foam plastic insulation are materials of concern because of the amount of energy required to create them, also known as embodied energy. Reducing the energy needed to create construction material will reduce the related GHG emissions. Production of Portland cement, in particular, is a very energy intensive process. An emerging area of opportunity is research at MIT and elsewhere, which has identified far less carbon-intensive alternatives and methods of making concrete that can actually use carbon dioxide as an ingredient, sequestering significant amounts. The Low Embodied Carbon Concrete Act was passed by the NYS Legislature in June, 2021 with a requirement for the state to develop a program for specifying this product for state-funded construction projects. A specific product, the Rivertown Low Carbon Concrete Sidewalk Mix, was developed by members of the consortium OpenAir in partnership with the Village of Hastings on Hudson, utilizing locally available ground glass pozzolan as a substitute for Portland cement. This mix was piloted by the City of New York and extensively tested. It can now be implemented by any municipality or developer at competitive cost.

Other ways to lower the embodied energy in building materials is to use materials such as mass timber, cross laminated timber, hemp lime and wood fiber insulation. Building materials with high recycled content are also preferable. Today, buildings can be designed to sequester more greenhouse gases than they produce – an opportunity worth pursuing through local policies and outreach to the construction industries.

On the social side of the building and construction industries, also, there is growing recognition of human rights issues. Globally, 25 million people are subject to forced labor, and child labor involves 152 million children. The Design For Freedom has convened a Working Group of 60 prominent leaders in architecture, engineering, construction and the international building materials supply chain, intimately connected to the construction industry and the sourcing of building materials. They have created a framework for challenging forced labor in these industries, setting achievable goals and creating tools including standards, auditing practices, big data, and business models. This is not typically considered as part of the building materials supply chain, but to the extent that Hudson Valley contractors purchase their materials at conventional big box suppliers, the issue should be considered and as much data brought to light as possible.

One source of regional focus and momentum would be a project to create model local building codes to maximize incentives for use of sustainable building materials, and especially low embodied carbon building and structural materials. The potential for developing a Hudson Valley based green building and structural materials industry cluster should be assessed through work with economic development agencies toward the goal by 2040 of supplying a majority of building and structural materials for the region, from within the region, through materials research, product design and reuse strategies. For example, timber is a low embodied carbon building material that is already produced in the region’s forests, and healthy forests are an essential foundation for carbon sequestration.

The lowest-carbon building materials are those that are reclaimed and reused from existing materials streams, including both surplus and reclaimed materials through deconstruction of existing buildings, rather than demolition. Deconstruction is often more labor-intensive than conventional demolition, but uses less energy and provides the revenue stream of reclaimed materials, contributing to its economic viability. Over the years, committed craftspeople have developed cost-effective deconstruction methods, such as dismantling buildings but leaving walls intact for reuse as “post-fab” panels for creating sheds and other structures. In some communities such as Portland, Oregon, local ordinances require deconstruction of historic buildings and those built during periods when asbestos and other hazardous materials were in wide use. A gentle incentive to develop a deconstruction industry would be for local and county governments to require deconstruction - or even feasibility studies for it - for public buildings.

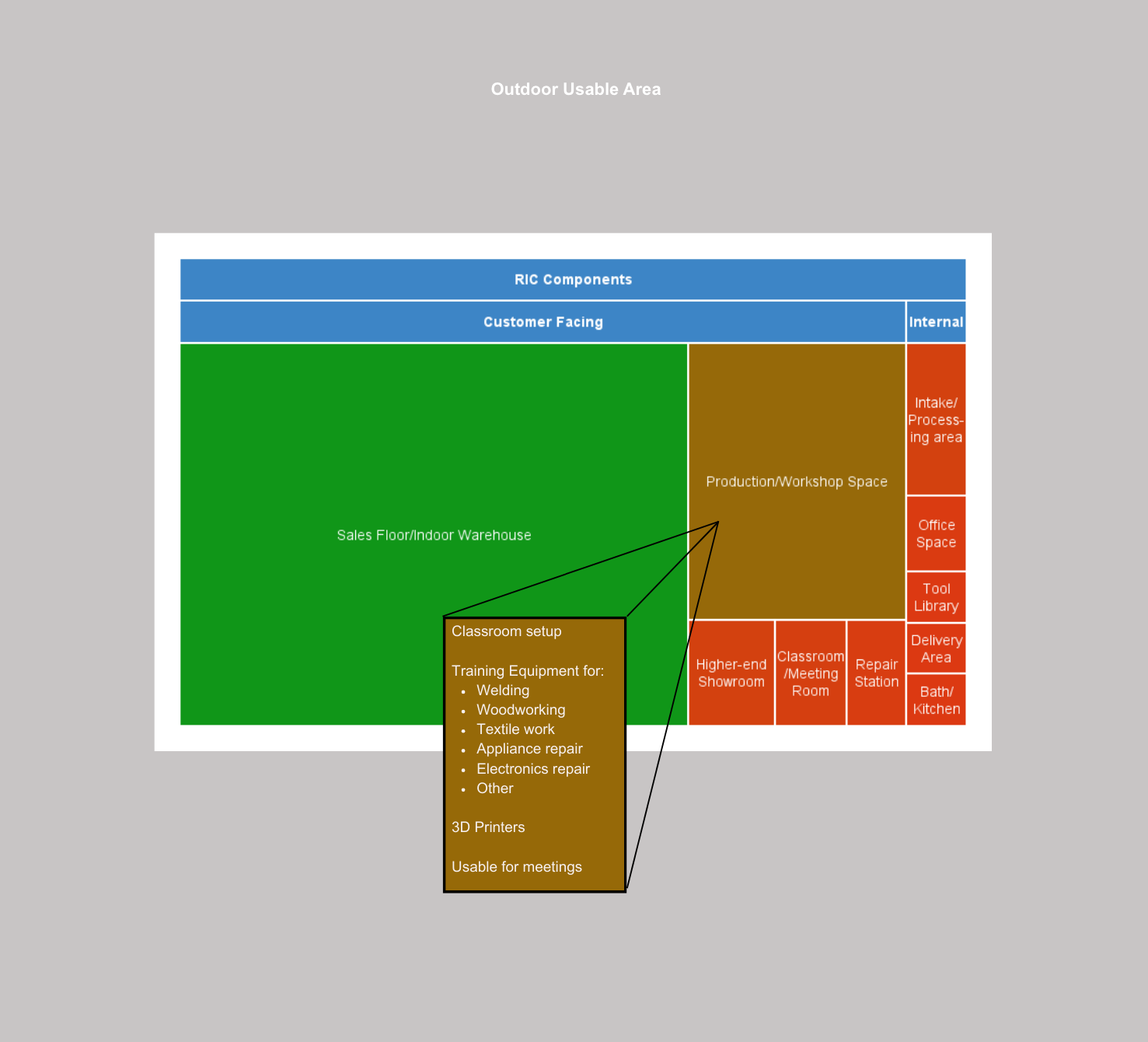

Ulster County has developed a strategic plan for a Reuse Innovation Center, with funding from the Legislature. Its initial anchoring industry would be construction and demolition materials, chosen as the heaviest, bulkiest and most energy-intensive items now being landfilled, and for their often-high resale value. This might serve as a hub for a regional network of enterprises to collect and reuse high-value materials, connecting existing municipal services with the wider network of circular economy entrepreneurs that has come to life in the Hudson Valley. A large, “home depot style” used building materials outlet, with showroom, is proposed as the anchor with a deconstruction business and training program, upcycled craft enterprises, repair and training among the core operations. If this model an be demonstrated in Ulster county, it might serve as a replicable model for additional centers in other parts of the Hudson Valley.

Case Study: Reuse Innovation Center

Ulster County has developed a strategic plan for a Reuse Innovation Center, and has tasked the Ulster County Resource Recovery Agency with implementing the plan.

The Reuse Innovation Center’s function is to build the circular economy by encouraging the creative reuse of materials at a significant scale. Designed to include over 100,000 square feet of retail space to sell salvaged and surplus building materials, textiles, and much more, the RIC will provide a collaborative space for small businesses, a showroom, training center, specialized recycling facilities and more. Its initial anchoring industry would be construction and demolition materials, chosen as the heaviest, bulkiest and most energy-intensive items now being landfilled, and for their often-high resale value. This might serve as a hub for a regional network of enterprises to collect and reuse high-value materials, connecting existing municipal services with the wider network of circular economy entrepreneurs that has come to life in the Hudson Valley. A large, “home depot style” used building materials outlet, with showroom, is proposed as the anchor with a deconstruction business and training program, upcycled craft enterprises, repair and training among the core operations. If this model can be demonstrated in Ulster county, it might serve as a replicable model for additional centers in other parts of the Hudson Valley.

Organics

Organics in the waste stream are emphasized in the waste discussion in the Scoping Plan because of their contribution to landfill methane and their weight as a material to transport. Food waste is a large part of the organics waste stream which we call attention to with a specific strategy in light of recent legislation and the easy composting of these materials in backyards as well as large facilities. There are new regulations, (6 NYCRR Part 350) implementing the requirements outlined in the Food Donation and Food Scraps Recycling Law enacted in 2019. State policy exempts health care facilities and schools, and sets a two ton threshold, but there is no reason not to encourage participation of these institutions and smaller generators as well. Local composting programs are being founded by more and more municipalities, and as they develop systems, it will be easier for others to follow.

Since January 1, 2022, state law has required large generators of food scraps to donate excess edible food and recycle all remaining food scraps if they are located within 25 miles of an organics recycler (composting facility or anaerobic digester). Counties are investing significantly in composting facilities and programs. Private composting businesses showing staying power include Greenway Environmental Services and Community Composting.

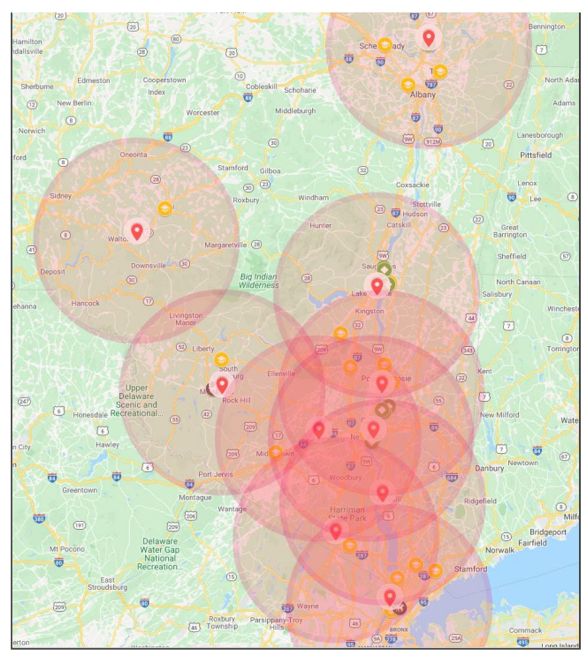

Biogas, produced by anaerobic digestion, shows potential for the replacement of fossil fuels for hard-to-electrify transportation uses and for power generation where it is produced (for example, in wastewater treatment settings). Research indicates that approximately ten anaerobic digesters, distributed around population centers, could meet this need. Constructing such facilities could be funded by federal or state infrastructure funds or specialized sources such as the Environmental Facilities Corporation’s Green Innovations Grant Program. It appears to be a matter of organizing the effort and raising funds to develop the infrastructure; regional impacts could be achieved even through incremental steps.

Biochar is also attracting attention as a value-added product that can be created from organic materials by means of pyrolysis, an anaerobic thermal process that – unlike combustion – does not produce air emissions. Biochar is recommended as an aspect of regenerative agricultural practice further on in our analysis. Because it sequesters carbon for 100 years and more – unlike compost or biogas - it can serve as part of a strategy for long-term removal of CO2 from the atmosphere.

Conceptual design of placement of 10 anaerobic digesters around the Mid-Hudson Valley for complete coverage bringing the entire region into a 25-mile radius of a facility. Nicholas P. Catania, “Hudson Valley Biogas” thesis, U Trondheim, Norway, 2022.

Repair Revolution A straightforward option to reduce waste generation is to prolong the life cycle of products by making it common practice to repair them. The Hudson Valley is fortunate to have one of the largest networks of Repair Cafes in the United States. Forty-five separate groups around our region regularly hold these gatherings, where people bring their “beloved but broken items and get help fixing them by an expert who is also their neighbor.” The Waste Advisory Panel of New York’s Climate Act included support of repair practices and trades as one of their recommendations, including programs teaching repair in the schools.

Repair Revolution, by John Wackman and Elizabeth Knight, shows the enormous educational and economic potential in the repair movement today. The Repair Cafe can thrive with very modest administrative and marketing support. Repair Cafes typically collaborate with and support local repair and reuse businesses such as shoe, bicycle, computer and appliance and furniture repair shops by drawing on their experts as Cafe volunteer fixers. There is interest growing in the Repair Café community to develop, pilot and disseminate a model curriculum for repair skill building in public schools across the K-12 grades and in community colleges. In 2022, 65 sessions were held, diverting over 3,000 items from the landfill and fixing 75% of items on the spot. The visibility of this effort is reflected in the Repair Café’s invitation to appear as a guest on the Today Show for Earth Day 2023, simulating an actual Repair Café on television.

Designing Systems for Circularity

Without changes to the system, conventional consumer recycling is unlikely to increase significantly. And recycling alone does not address the climate impacts of materials throughout their lifecycle. Many Hudson Valley municipalities truck their trash far across the state to the Seneca Meadows landfill, mainly using polluting diesel fuel. This facility is nearing capacity, and the host community is grappling with its continuing role. This leads us to propose a systems shift toward expanded commitment to stop transporting waste out of the area and instead build consensus for local solutions. And compared to siting new landfills, the politically much more attractive opportunity is to redesign our production systems and create a circular economy.

Unlike the predominant ‘take-make-waste’ system, a circular economy is one where used products and waste material are cycled back into the production system to create new products. The circular economy system is described by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a global hub promoting circularity, as:

“...the continuous flow of materials in a circular economy. There are two main cycles – the technical cycle and the biological cycle. In the technical cycle, products and materials are kept in circulation through processes such as reuse, repair, remanufacture and recycling. In the biological cycle, the nutrients from biodegradable materials are returned to the Earth to regenerate nature.”

The carbon footprint of “stuff” is large and under-appreciated. Making and distributing consumer goods is an energy intensive process. Governor Hochul’s 2022 State of the State address noted that waste-management activities contribute 12% of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, and called for a variety of zero waste strategies. Materials management and waste reduction are strong themes in the Final Scoping Plan.

The materials management system in the Hudson Valley is complex, involving numerous county, local and private programs and services with limited coordination. While New York announced a statewide recycling rate of 90% in 2021, many recycled materials are shipped outside the region rather than feeding industries within it. Significant contaminated materials – including would-be recyclables, are shipped from the Hudson Valley to the Seneca Meadows landfill in Central New York, a facility that is nearly at its capacity. Many recyclable and reusable materials end up in landfills due to depressed markets, the complexities of processing or the availability of options for recycling-based industries.

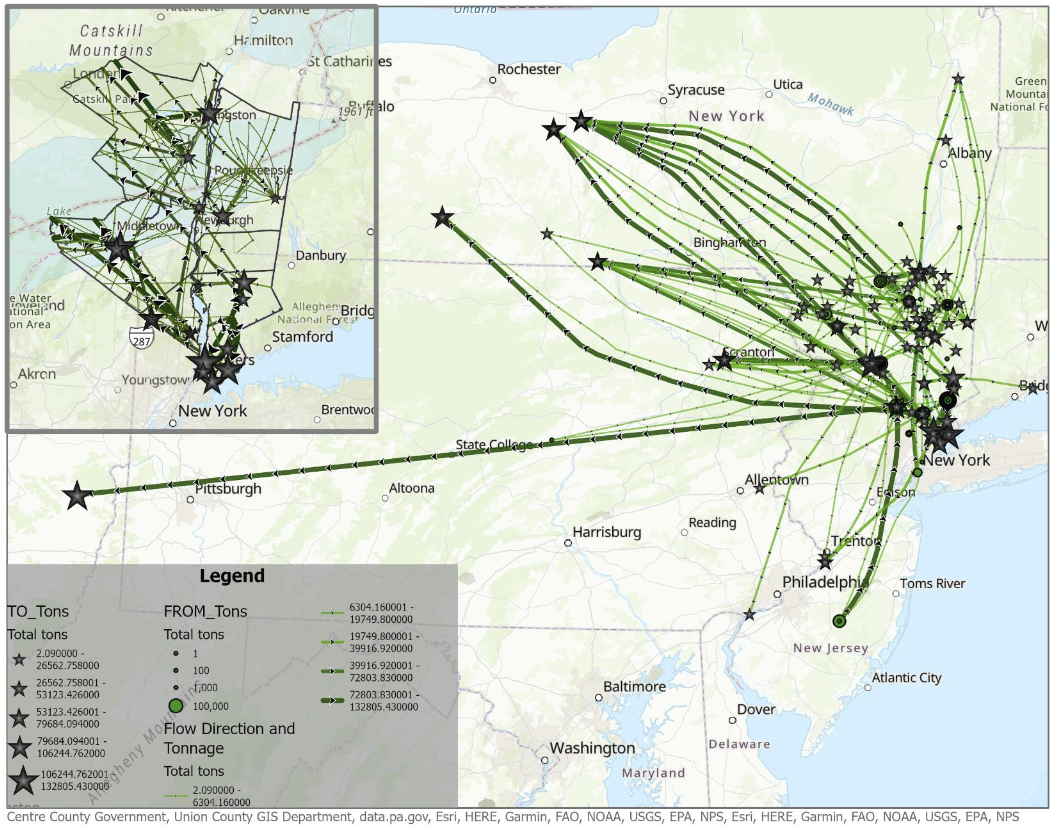

Flow of Municipal Solid Waste and Construction/Demolition Products from the Hudson Valley

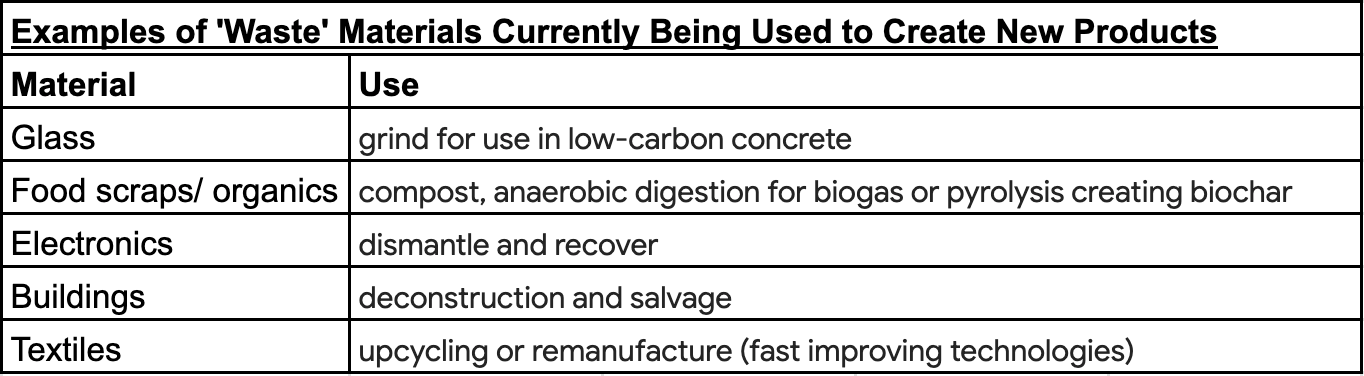

Creating a circular economy will require new levels of creativity and collaboration to increase diversion of materials from the waste stream for use in the production of new materials and products. Regional cooperation has begun to identify new markets for materials that had been shipped out of the region, including glass for use in low-carbon concrete; cooperation may also contribute to better economics for processing these materials. Because local capacity is often constrained by lack of bricks-and-mortar facilities for collecting and processing materials, county and local attention to infrastructure is needed. But cooperation between counties can provide a work-around to deal with infrastructure limitations in some county resource recovery agencies and transfer stations. And at this moment, with significant funding available for public infrastructure, it could not be more timely to consider how to develop the necessary infrastructure to maximize materials recovery in the Hudson Valley region for use in the region, and building new recycling-based industries.

Inventory Material Flows and Infrastructure

The first step in planning circular economy initiatives is to inventory and characterize the materials flows in, to and from our region, in order to come up with sector-by-sector opportunities for industries based on reuse, remanufacturing and recycling. A pilot waste flow mapping project was conducted for this initiative using 2020 county reports to the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation. A second key activity is to inventory materials management infrastructure, such as transfer stations and processing facilities. This map identifies publicly owned facilities, providing a foundation for understanding the capacity of existing infrastructure.

Reuse-based industries, turning surplus and discarded materials into new products, could be a high-impact part of a circular regional economy, reducing emissions by reducing the need for new products as well as by reducing waste transportation to the landfill.

A full inventory would include not only materials generated in our region, but materials shipped to our region in quantity from elsewhere, such as a high volume of construction and demolition waste from New York City that is regularly sent to locations in Columbia and Greene Counties.

Most of these approaches are already in use in the Hudson Valley. For example, Rockland County’s wastewater treatment plant is powered by biogas from anaerobic digestion onsite. Helpsy is a Certified B Corporation that collects and repurposes textiles, prioritizing upcycling and remanufacture at US-based facilities. Pozzotive is a Westchester based company that reprocesses glass for use in low-carbon concrete.

A foundation for this effort will be political will among Hudson Valley counties and solid waste authorities to stop transporting waste and commit to a regional Zero Waste resource recovery and circular economy strategy.

The concept of a circular economy, designed to maximize societal benefits and regenerate the environment, is coming into circulation and being demonstrated by major organizations including Renault and Coca-Cola, the largest user of single-use plastics, which is piloting a return to glass bottles in Europe and could easily do so here in support of the recent public groundswell against wasteful packaging. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation:

Looking beyond the current take-make-waste extractive industrial model, a circular economy aims to redefine growth, focusing on positive society-wide benefits. It entails gradually decoupling economic activity from the consumption of finite resources, and designing waste out of the system. Underpinned by a transition to renewable energy sources, the circular model builds economic, natural, and social capital. It is based on three principles:

Design out waste and pollution

Keep products and materials in use

Regenerate natural systems.

Case Study: NYC Circular City Initiative

The NYC Circular City Initiative is a comprehensive effort to transform New York City’s economy into one that predominantly operates in a circular mode, with reuse and recycling as the “new normal.” This undertaking is hard to imagine, but may be more possible by virtue of the density of the City and complexity of the systems that make it run. Published in 2022 with significant involvement of the New York City Economic Development Administration, the plan is based on ten levers of change:

Markets – developing markets to recycle more materials;

Procurement – using government procurement of recycled goods to build demand;

Extended Producer Responsibility – requiring design for recyclability and, in some cases, producer financial responsibility for assisting with collection;

Jobs - building understanding of the work opportunities across the circular economy in reuse- and recycling-based industries, and leveraging workforce development funding to grow circular businesses;

Planning - planning for land use, infrastructure and economic development initiatives that increase circularity;

Finance – developing new revenue streams and financial incentives;

Policy - advancing policy to make circular practices easier;

Innovation – solving problems with new processes and models;

Communication – widely share the benefits of circularity with the public through many channels;

Education – bring this same understanding into curricula throughout the educational system.

Circular economy models are most advanced in Europe, but the overarching methods and tools are completely applicable in our region. New York City recently published a comprehensive circular economy strategy using the powers of local government such as procurement policies and catalytic projects.

The Ten Levers of Change: NYC Circular City Initiative

Markets: Build on, develop and promote existing materials marketplaces around the city

Procurement: Develop procurement guidelines and set targets for circular procurement.

Extended Producer Responsibility: Ensure manufacturers take financial or physical responsibility for the treatment or disposal of post-consumer products.

Jobs: Develop a jobs plan to identify, facilitate and promote circular jobs around the city.

Planning: Incorporate circular economy principles into zoning and land development policy.

Finance: Develop mechanisms and policy incentives to support the financing of circular economy (CE) technologies, projects and start-ups.

Policy: Develop policy to incentivize good (e.g. reduced sales tax, circular goods marketplaces) and disincentivize bad (e.g. “pay-as-you-throw”) practices.

Innovation: Promote circular innovation in product design, production processes and business models and through bespoke projects and ideation programs.

Communication: Develop campaigns to communicate the benefits of circularity to residents and businesses and highlight the good work already being done.

Education: Integrate circular thinking into the curriculum for vocational training and at universities and business schools.

This could serve as a foundation for planning in the Hudson Valley. In fact, as materials from the City often flow to the Valley - including construction and demolition waste - it is hard to imagine how New York City’s circular economy strategy will be successful without involving its neighbors to the north.

To capture the circular economy opportunity, planning and coordination will need to involve both government and private interests that are part of the current materials management system and its regulation. This includes Resource Recovery Agencies, potentially through their joint Materials Management Work Group, coordinated by the Hudson Valley Regional Council and representing all the resource recovery agencies of the Mid-Hudson counties. A realistic approach might be to identify one divertable material at a time, that can feed a circular process, and collaborate across counties to design strategies and build a market for one product category at a time.

The timeline for implementing these recommendations should be set to take advantage of the major changes in incentives and resources that will take place as the state’s Cap and Invest program is finalized, which will increase the cost of petroleum-intensive, inefficient and unnecessary transportation of waste and create greater incentives for circular solutions that turn waste to usable resources near the location where it is produced. Analysis of waste streams and opportunities for capturing, diverting and use as feedstocks for new products is the first step in redesigning a circular materials management system. County resource managers substantially understand this. Identifying opportunities for regional collaboration to redesign systems and capture economies of scale is the next step on the path.

Imagine the path forward

As we consider how to achieve deep decarbonization and widely shared benefits, how will we implement the needed changes? What barriers need to be overcome? What assets need to be mobilized? What partnerships are needed? What will the work look like, year by year?